Instead of being a place to “dry out,” my prison now often perpetuates addiction.

Instead of being a place to “dry out,” my prison now often perpetuates addiction.

by Christopher DankovichApril 1, 2025

Prison Journalism Project

Prison Journalism Project

Donate

Posted inFeature

The Rapid Rise of K2 and Suboxone in a Michigan Prison

Instead of being a place to “dry out,” my prison now often perpetuates addiction.

by Christopher Dankovich

April 1, 2025

Republish This Story

FacebookXBlueskyLinkedInWhatsAppEmailPrint

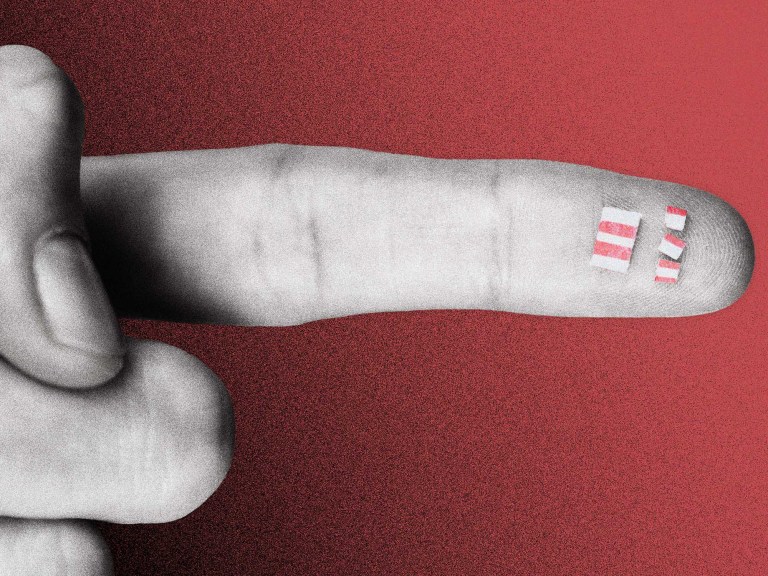

A photo illustration shows a fingertip holding paper tabs laced with drugs.

Photo illustration by Sarah Rogers. Photo from Adobe Stock

“Hey, man,” someone whispered as I passed him on the prison track. He said it so quietly I wasn’t sure he had said anything, but then, “Hey, you — yeah, you.”

He was a very large man, covered in gang tattoos.

“Sup?” I responded, curtly, puffing my shoulders a bit.

“Let me holla at you for a hot second.”

“Whatchu want?” I asked.

Years ago, during the early days of my prison sentence, I had people try to mess with me, scare me, extort me, sexually intimidate me, threaten me and fight me. It generally started with someone speaking to me like this man did.

He kept at it, but looked around anxiously. We were on the distant side of the recreation yard, as far from guards and any of my friends as it was possible to be — safe for him, but no help for me.

“Man, just to let you know, I got that two-ski. I got good prices,” he said.

I relaxed. He was referring to the synthetic hallucinogen known as “paper” or K2. Perhaps I should have expected it, as this type of behavior had become typical in my Michigan prison. I turned down the drugs, but I’m sure he found a buyer eventually.

Two drugs in particular have flooded my prison and others around the country in recent years. Those drugs are the aforementioned K2 and the less common, but still prevalent anti-opiate medication Suboxone. Almost every day I have to turn down strangers trying to sell me the stuff.

Instead of being a place to “dry out,” my prison often perpetuates addiction. Drugs are smuggled in and easy to find.

In prison, we stew all day, enclosed in a concrete box, interacting with miserable people. It’s no wonder people desire an altered consciousness. The prison drug trade takes advantage of this desperation, exacerbating already-dire substance abuse problems.

Prison staff and prisoners face never-before-seen threats to their safety from erratic and unpredictable users, almost all of whom will leave prison in coming years. What those who work and live in prison face today, society will face tomorrow.

How drugs get in

The prison drug trade is not too complicated to understand. Some of the drugs get in legally, including through legitimate Suboxone prescriptions available in Michigan prisons. Drugs also get in illegally, typically in one of several ways: thrown over the fence, concealed in mail, or smuggled in during a visit or by prison staff.

I’ve been on the prison yard when the emergency siren erupted because someone flew a drone over the fence to air-drop drugs. I’ve seen tennis balls packed full of dope land in the yard, slung from far on the other side of the fence. Unfortunately for the intended recipient, the one I witnessed was intercepted by officers.

Another time I was on a visit when a prisoner in the next seat pushed a small package into the crotch of his pants.

And I watched as someone I vaguely knew got prison-rich off of a letter onto which his family had melted hundreds of doses of Suboxone.

In response to the influx, a dozen cameras were installed in the visiting room, which is about the size of a two-car garage, to stop drugs coming in on visits. This is in addition to the mandatory frisks of visitors beforehand and strip searches of all prisoners after visits.

Tobacco products have also been banned. Dogs trained to sniff out drugs and tobacco are periodically brought through the prison and our cells. Officers regularly search the cells and bodies of suspected drug dealers and users.

The COVID-19 pandemic heightened supply and demand in the prison drug trade. For the first month of the pandemic, the drug supply was curtailed in my prison. Visits were completely stopped to prevent the spread of the disease. Mail was no longer delivered to prisoners except as photocopies. Sensors, cameras and drone detectors had previously been set up en masse around the perimeters of all Michigan prisons, so that kind of smuggling had been cut off.

Only one viable route remained: smuggling by officers. Michigan is hardly the only state having to confront this problem in recent years. In jails, state prisons and federal prisons across the country — from Georgia to Alaska and everywhere in between — guards have been arrested for suspected drug smuggling since the onset of the pandemic.

The Michigan Department of Corrections did not respond to a series of questions from a Prison Journalism Project editor.

The rise of Suboxone

“Give me Suboxone or I will not eat! Give me Suboxone or you will not sleep! Suboxone, Suboxone, I need Suboxone. I need it, baaaad!”

E.C. had a terrible singing voice, but his song was pretty funny. I was in an isolated cell in 2022 after testing positive for COVID-19. He was also in isolation after getting caught with drugs.

Keep this journalism independent. Your donation is matched x2 today!

Donate

Over the past decade, Suboxone has become one of the most popular drugs in Michigan prisons. The drug comes as a sublingual strip and is a lauded treatment for opiate dependency. But it still contains a partial opiate that can cause mild euphoria.

Designed to melt in your mouth like mouthwash strips, Suboxone can easily be dissolved onto paper and thus concealed in bulk amounts. Prison smugglers regularly bring in 100 or even 1,000 strips at a time.

On the outside, the Michigan street value of one Suboxone strip is around $5. In prison, each strip is worth $75 to $150 when sold whole. Resellers then cut the strip into “quarters,” each of which sells for $25 to $40.

The drug is so potent that many people buy a quarter and cut it smaller, using only a piece at a time. For maximum effect, users place the piece in their eye or dissolve it in water and snort the liquid.

Suboxone has such high profit margins that I have heard it called “prison heroin.”

The state prison system often sends mass notifications via JPay, an e-communication platform, alerting us to disciplinary warnings, drug seizures and the increase of positive drug tests. For the past five years, in every cellblock I’ve lived in, I’ve witnessed a dozen people or more each month either test positive for Suboxone or disciplined for possessing it.

The rise of K2

During the pandemic, synthetic cannabinoids exploded onto the scene. They are easily the most frequently used drug in my prison; I estimate that at least 25% of the population use it daily, with many others being semi-regular users. In here, it’s commonly referred to by the name of the former top-selling brand, K2.

K2 is usually smoked in our communal bathrooms. Every bathroom in every cellblock I’ve been in smells constantly like burnt bug spray, the K2 signature. And every single day, someone suffers a mental crisis after smoking it and is found with a prison-made lighter and a tube to smoke out of.

One day in August 2023, I watched as officers pulled a man — someone I have known for years and never knew to be much of a user — out of the communal bathroom. He was screaming. He had large, bloody gashes on his face, presumably from clawing himself. He was twitching as staff led him, hands cuffed behind his back, to the health care unit.

He eventually told me that he had been smoking K2.

An ordinary sheet of paper can contain a thousand hits of synthetic cannabinoids, which are tasteless, scentless and clear. It is sprayed on paper and dried. The user smokes bits of the paper. A piece the size of a quarter of your pinkie nail contains enough of the drug to get someone intoxicated.

A vial of liquid that costs about $75 can cover between five and 10 sheets of paper, which are often smuggled into prison disguised as notes or a page of a book — with each sheet selling for $500 to $1,000. Still, a person can get intoxicated for as little as a dollar or two.

Depending on what’s in it, a dose strong enough to produce face-clawing hallucinations is about the size of a quarter of your thumbnail. For $10, you can get two of these. Some quick hustling — selling prison-issued meals to incarcerated workout fanatics, for example, or a little thieving from the mess hall — can get you high on “two-ski” every day.

Dozens, if not hundreds, of people in this prison compensated for two years of COVID-19 prison lockdowns by spending their entire federal stimulus checks on a few weeks’ worth of K2.

Selling drugs in prison can be lucrative and getting high is, for many, a necessity. But the downsides are evident. The day I wrote this article, an ambulance pulled into my prison, as I estimate it does at least once a week for various reasons, but especially drug overdoses.

Watching from the yard, where I was hanging out with my friend Yoshi and the rescue dog he was training, I saw paramedics run into C Unit with an empty stretcher and come out with a middle-aged man. He seized as he was wheeled to the ambulance. He had just smoked K2.

Comments